If you are near a production or manufacturing line, here’s an easy and instructive exercise. Each time you’re on the line, stop for a minute or two and count the number of operators you see waiting.

Do this for a few days, take an average of your observations and express that as a percentage. Now you have an estimate of the potential productivity improvement that you’d see if only you enabled your employees to have something to work on all the time. There’s often opportunity beyond this simple view: in addition to the folks who are visibly waiting, many more line operators will have consciously or unconsciously slowed down to match their neighbor’s rate and avoid the need to stand and wait.

In my experience of dozens of implementations of this technique, companies have achieved productivity benefits ranging from 10% to 40%.

How can we eliminate waiting? Step 1: go to lunch.

Observe the local sandwich place (or burrito place, depending on your taste) at a busy lunchtime. The sandwich store I often go to is perennially understaffed – there are 4 places to work behind the counter, but never more than 3 staff. These 3 workers constantly move back and forth between workstations to keep sandwiches (and customers) moving towards the cash register. They have no room to let any more than 1 or 2 half-built sandwiches build up between workstations (and hungry customers would get peeved pretty quickly) so those sandwiches keep moving. As soon as the first sandwich-maker has one sandwich ready for the next station, he or she builds the next one and then moves downstream to the second station. Often, by the time he or she has worked on just one sandwich at the second station, it’s time to move back to station #1.

Note that all this movement is not directed by a manager, andon lights or anything sophisticated – other than the ever-present need to keep hungry customers (and their sandwiches) moving toward the register.

This same objective applies in manufacturing. With adequate line design, and a few simple tools, we can help line workers automatically move to always be in the best location to a) support customer demand, and b) be productive.

Visual Signals between Workstations

First, we need to establish a visual signal to tell operators when to move to a different workstation. This signal can be something as simple as a painted colored rectangle on the floor or production line between workstations. Often this visual signal is called an ‘In-Process-Kanban’ (IPK).

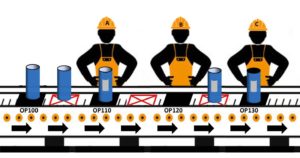

Figure 1

Figure 1

In Figure 1 above, the IPKs are represented by a red square with an ‘X’. Each IPK holds one piece. 1-piece IPKs are common, but there are many instances where IPKs need to be larger to accommodate greater time imbalances between workstations (the calculation of IPK sizes is another topic – we’ll cover that separately). Whatever the size of the IPK, it represents a maximum quantity. When the IPK is full, and the next unit at the workstation is complete (i.e. the workstation is ‘full’), this provides a clear visual signal of a bottleneck.

Flex

In Figure 1, it’s quite clear that the line will not flow unless someone works at OP120. Operator B has the clear signal to flex into OP120, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Another scenario is shown in Figure 3. Operator B has no product to work on, either in the workstation or in the upstream IPK. Clearly, the IPK signal is for Operator B to flex back upstream to OP110. Each operator will follow the signals like this all day.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Sounds simple…

Operator flexing like this is pretty simple, until you reach a situation like the one shown in Figure 4. In this scenario, Operator B again has a signal to flex upstream to OP110 – but Operator A is working at OP110.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Here we have 2 options:

- Aid and Assist. Operator B helps Operator A to work on the unit at OP110. This is often very feasible for large products. Even in machine-based environments, Operator B may be able to help by getting the next setup ready or loading material.

- Bump. If not, then either Operator A or Operator B should flex out of OP110 and into OP100. Generally, the better choice would be Operator A as he/she would be more likely to be trained in this operation than would be Operator B. However, there may be exceptions and each line has to establish and document the flexing rules for these situations.

Outcomes

- In well-trained and disciplined lines, productivity improvements from operator flexing typically exceed 10%.

- Easier for line leaders to see issues in real-time. When IPKs fill up at a particular workstation, it clearly indicates a problem of some sort. For line leaders, this real-time indication is invaluable – we can be at the source of the problem while it is still occurring, not hours later when we see the results in end-of-line output.

Prerequisites

- Cross-training. Operators should be trained in at least 3 operations, though more is better. Where operators cannot flex to a particular operation (for e.g. because of a lack of training, qualifications or work rules), the line generally needs larger IPKs and does not gain in productivity at that location.

- Vacant workstations. A flexing line runs best when there are vacant workstations to flex into; the maximum productivity typically occurs when a line is 80% staffed (i.e. 20% of workstations are vacant).

- Make it easy for the operators to flex. For example:

- IPKs clearly marked, with maximum quantities easy to see.

- Distances between workstations should be as short as possible

- Pathways between workstations should not be obstructed (inventory, walls, material, cabinets, machinery, conduit or piping)

- Tools, equipment and methods should be standardized (and not personalized) across workstations. Flexing is much easier to implement when operators perform work standing, not seated.

- Standard work exists – at least to the extent that the work at a workstation is clearly defined.

- Training & Reinforcement. To state the obvious, flexing is a new skill for most people. It is important to train everyone in the new rules. I’d recommend posting diagrams of the different scenarios at every workstation, and provide a copy for everyone. To begin with, line leaders should spend at least 15 mins a couple times a shift just watching operator movement on the line… and provide positive feedback each day to each operator who is flexing correctly. Very importantly, a line leader should never walk past an overfilled IPK without investigating.

Operator flexing is one of the most significant productivity improvements available to most manufacturers without significant process change or automation. The best part – it utilizes your employees’ natural flexibility and ability to switch tasks rapidly.

For more information, visit us at www.praestoleansolutions.com , email at info@praestoleansolutions.com, or call at +1 720 891 2829